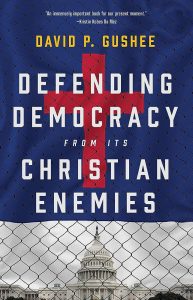

This week, my new book, Defending Democracy from its Christian Enemies, officially releases. I am told that even before its release, it exceeded the publisher’s sales expectations for one full year. I am grateful for the high interest in the book. In this post, I want to review its main arguments.

My thesis is that many Christians in the United States and elsewhere today are demonstrating an attraction to a dangerous authoritarian and reactionary politics that poses a grave threat to free and open democracy. My book is a warning about what political scientists call democratic “backsliding” or “deconsolidation,” especially where that democratic erosion is aided and abetted by Christians who are abandoning pro-democratic Christian traditions that are centuries old.

Why I wrote it

Writing this book was motivated by the shocking events in the U.S. that culminated in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection — but that had been brewing for some time. Those events do involve the anti-democratic tactics to which former President Donald Trump resorted when he could not hold on to power any other way. But deeper examination, especially of the strong support of many reactionary Christians for everything he did, including insurrection, reveals deeper and longer-term dynamics that must be explored. Undertaking that exploration led to growing awareness on my part that these dynamics are not confined to the U.S. but are international.

“These dynamics are not confined to the U.S. but are international.”

Our current democratic crisis reveals a need to revisit the very meaning of democracy. I follow standard contemporary political scientists in suggesting democracy is characterized by the rule of the people under the rule of law. That is, a democracy exists where the people and/or their representatives create the constitution under which they will live, write the panoply of laws that govern various aspects of their behavior, enshrine civil rights and civil liberties that protect individual and minority rights, and elect their own leaders through free, fair, contested elections decided by popular vote.

A wide range of norms, practices and rules, not just laws, protect democracy. As in other fields of human endeavor, so in democracy one can find best practices within a tradition developing over time. Pro-democracy groups like Freedom House offer numerous helpful guides as to these best practices.

Countries that claim to be democratic can be characterized as moving toward, holding steady or drifting away from these best practices. Concerned citizens should care about the direction of movement in their own country. Ours is trending in a bad direction.

Religious and Enlightenment roots

The modern Western democratic tradition is generally agreed by scholars to have both religious and Enlightenment roots. The religious roots came first. One way to trace them is to describe the proto-democratic stirrings visible in dissenting religious movements under established Christian governments, notably beginning in England with the Puritans and eventually the Baptists and others. These movements offered statements calling for limited state power, and civil rights for individuals and minorities, with special attention to religious liberty and freedom of conscience.

I argue in the book that Puritan covenantal thought and Baptist congregational-democratic commitments are still key resources we can retrieve today to renew the defense of democracy.

The Enlightenment roots of democracy are generally attributed to figures like Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, both of whom offered theories of government that moved away from top-down, theologically centered divine right of kings approaches toward the bottom-up decision of (some part of) the people to compact together to create governments with powers focused on securing their own “life, liberty and property.”

We can easily hear the echoes of this approach in the founding documents of the United States. The tradition is valuable but problematic in its lack of much of an account of citizen virtue or the common good.

“It is hard to overstate what a grand achievement it was for people to wrestle control of government away from monarchs, emperors, dictators and oligarchies and place it in the hands of the people under the rule of law.”

It is hard to overstate what a grand achievement it was for people to wrestle control of government away from monarchs, emperors, dictators and oligarchies and place it in the hands of the people under the rule of law. Despite a fascinating experiment with direct democracy in classical Athens, and a long effort at a kind of republican government in ancient Rome, it had been 1,600 years of imperial and monarchical rule since then, and before that and alongside that one tyrant after another in the ancient world.

Democratic revolutions in France and the United States in the late 18th century, as well as the very gradual democratization of the British government, helped set the stage for the birth of a modern world with spreading democracy. The turn to Communism in the early 20th century, and to fascism just afterward, marked a huge democratic setback. The defeat of the Axis powers during World War II, and the absolute degeneracy of the fascist governments that had been defeated, deeply discredited rightwing authoritarianism. Communism’s gradually revealed evils, and the collapse of the USSR and the Soviet bloc around 1990, did the same with that leftwing form of authoritarian rule.

History doesn’t stand still

It appeared democracy was about to be uncontested. But history doesn’t stand still. In the 21st century, we have seen signs of democratic backsliding or failure in multiple countries that had seemed secure in their democracies.

In the book, I discuss the failure of democracy to consolidate in Putin’s Russia, as well as democratic backsliding in Poland, Hungary, Brazil and the U.S. I also offer chapters comparing developments in Germany and France from the mid-19th century up to the fascist turn in the 1930s/40s that occurred in both countries.

I argue what all these countries had or have in common is a peculiar malady especially related to religious and moral traditionalism under pressure. I call this malady, in my own new coinage, “authoritarian reactionary Christian politics.”

It is reactionary in that it is characterized by ferocious negative reaction to cultural changes perceived to violate religious and moral traditions held by once-dominant Christian groups — like conservative Orthodox in Russia, Catholics in Poland or evangelicals and Catholics in the U.S. and Brazil. Close study also reveals in many cases the reaction goes beyond religious and moral concerns to matters of race and immigration.

Basically, what all the cases I have studied have in common is an allergic reaction to social, political and policy changes that create greater pluralism, weaken a majority Christian group’s dominance in culture and diminish the power of previously all-powerful groups to control the direction of culture, society and government.

Why reactionary?

What makes these reactionary movements authoritarian is two things.

On the one hand, they are often authoritarian in their inner life — their approach to religious truth, moral rules and church organization is through centralizing power in a dominant person or small group.

But, on the other hand, what makes this inner authoritarianism relevant to everyone else in their society is that they might and sometimes do refuse to support or withdraw their support from (the practices of) democracy when they are consistently frustrated with the results. They might throw their support behind a Christian strongman who promises them what they want. They might even find themselves breaching the U.S. Capitol when the election results are not what they wanted.

I notice in the literature a dynamic that political scientist Michael Walzer has called “secular revolution/religious counterrevolution.” In a 2015 book, he described how that had happened in Algeria, India and Israel. I suggest that for the first time in American history it is what we are witnessing here. The secular revolution is (perceived to be) pretty much every liberalizing, pluralizing, democratizing social change since the 1960s.

The religious counterrevolution has been brewing since the same period. It began as an effort to take America back through evangelism and missions. That failed. It moved to a political effort to take America back through the Christian Right’s alliance with the Republican Party. Despite Reagan, despite the Bushes, that also was perceived to have failed.

There always was an unattractive underbelly of racism, xenophobia and threats of violence on the militant right. This underbelly, which goes very deep in American history, now has been activated in some truly frightening ways.

If Christian mission fails, and democracy fails, and you can’t win the game any other way, maybe you try something else. There is frank exploration by scholars and others in which we can see people seriously reconsidering the democratic rules of the game in this country with an openness I have not seen in my lifetime.

But what can we do?

Many see the problem. What do we do about it? We need to begin by calling things by their right names. Authoritarian reactionary Christianity is the right name. We also need to clearly see the distinction between reactionary strategies that stay within the boundaries of democracy and those that transgress them. Jerry Falwell was one thing; the Proud Boys were another.

Meanwhile, concerned citizens need to pay attention to the basics of democracy in a way most of us never have bothered to do — at least not what may have been a poorly taught high school government class. We need to know what distinguishes a democratic government from an authoritarian one, and democratic politicians from those who are striking anti-democratic notes.

“The way of Christ does not get suspended in what some may perceive to be emergencies.”

And we need to go back to school on our own best traditions. For more than 400 years, congregationalist, baptistic democracy has taught ordinary people how to govern themselves, while in the public space pro-democracy Baptists/congregationalists have argued strongly against theocracy, authoritarianism, religious establishment and Christianity as a domineering and imperious majority project.

Covenantal theologies (at their best) emerging from a strand of Puritans and Baptists taught us to think of public life not as a dynastic project, nor as an individualistic libertarianism, but as a compact made by equals to advance the common good of all. And the dissenting Black democratic tradition in the U.S. has for our entire history pointed out the desperate flaws built into the U.S. version of democracy, as it from the beginning accepted slavery and enshrined white supremacism. Their call for a reformed democratic covenant in which all are at last included on equal terms is desperately relevant today.

Today, Christians need to remember that Christ is Lord and that the way of Christ does not get suspended in what some may perceive to be emergencies. We need to recall the pro-democratic resources that can be mined from Scripture.

We must reconnect with centuries-old democratic strands of the Christian historical tradition. We can reject authoritarianism because we know God is against tyranny and because absolute power corrupts absolutely. We can remember how bad it was when religious majorities were able to impose their beliefs in violation of the consciences of dissenters. We can learn to live in societies with profound diversity of beliefs, asking what God wants to teach us through others.

We can remember God’s concern for those on the margins and recoil at any politician who attacks marginalized groups for political gain. We can resolutely resist a politics of cruelty and domination. We can renew our commitment to the rights of our fellow citizens as a recognition of how much God loves all people.

We can recommit to personal virtue and democratic participation. We can stand against deteriorations of Christian identity such as faux Christian nationalism, racism, sexism, xenophobia and contempt for LGBTQ people.

We can love our neighbors by doing justice in politics. We can and must resist authoritarian reactionary Christianity, not just with our words but with our lives.

This article first appeared in Baptist News Global.