I am reading the Roman statesman-philosopher Cicero these days. You might ask why in the world that dusty old personage should be occupying my thoughts.

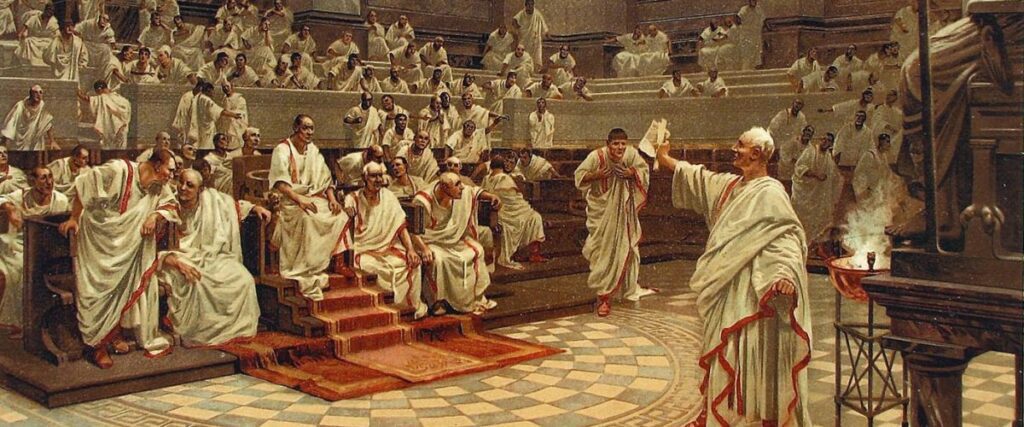

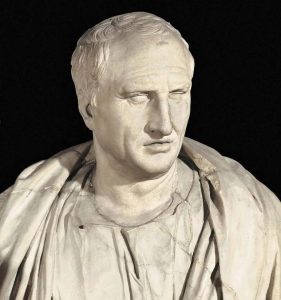

The answer is that, as part of the preparation of my new book on democracy, I am attempting to retrace the most significant lines of Western political thought. This month that has taken me back to Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE), the Roman senator whose writings about the governance of commonwealths, as well as the nature of law, have been highly influential in the development of the democratic-republican political tradition, including in this country.

Three primary contributions have become apparent in my reading of Cicero and about Cicero.

The first is the idea, offered in his book The Republic, that the best constitution for a commonwealth involves a “mixed” structure combining elements of kingship (the rule of the one), aristocracy (the rule of the noble) and democracy (the rule of the people as a whole). Cicero argued that each, on its own, has strengths, which he enumerates; but each also has vulnerabilities so profound they tend not to provide a stable basis for politics, instead giving way to successive revolutions.

However, says Cicero, a system “composed of an equal mixture of the three best forms of government, united and modified by one another,” could succeed where others tend to fail. Rather than the bloody mess of one revolution after another, it was possible to stabilize politics by incorporating the strengths, and avoiding the weaknesses, of the rule of one, the noble and the many. He believed this is what the Roman Republic was able to achieve. This proposal was influential in the development of the U.S. Constitution.

The second primary contribution of Cicero’s political thought, suggested in his later work, The Laws, is a rather compelling statement of a natural law concerning the basis and nature of civil law. Cicero argues theologically in this vein: God who made humans shares with humans the capacity for reason. This capacity for reason includes the ability to know what is right and just. Law’s ultimate origins lie here.

Civil law, rightly crafted, is not a matter of opinion, will or power but an effort to “command what is right and prohibit what is wrong,” in accordance with reason, molded by virtue and directed toward justice.

“Every law which deserves the name of a law, ought to be morally good and laudable.”

“Every law which deserves the name of a law, ought to be morally good and laudable,” says Cicero, advancing what is right and just. Laws that do not reflect the just distinction between right and wrong are not laws at all.

Martin Luther King drew on this heritage during the Civil Rights movement when he argued that “an unjust law is no law at all,” and thus civil disobedience was fully legitimate.

Cicero

While natural law is a highly contested concept, for good reason, it does seem preferable to any theory of law that simply says what makes a law legitimate is that the legitimate authority decreed it or a majority voted in its favor.

There is a rather sad third contribution of Cicero I want to flag here as well. Writing at the time when the Roman Republic was convulsed by constant violence and gradually deteriorating into what became an imperial dictatorship, Cicero laments the process of political decay he sees all around him.

His argument goes like this: Republican Rome was once shaped by customs (“manners”) that molded the character and behavior of virtuous leaders, and “admirable citizens, in return, gave new weight to the ancient customs and institutions of our commonwealth.” In other words, back in the day, a virtuous cycle of culture and leadership sustained a great republic. People knew what virtuous leadership and healthy political behavior looked like, leaders emerged who behaved accordingly and were honored for doing so, thus reinforcing the norms, and so on it went over many centuries.

But “our age,” says Cicero, “having received the commonwealth as a finished picture of another century, but one already beginning to fade through the lapse of years, has not only neglected to renew the colors of the original painting, but has not even cared to preserve its general form.”

“Cicero is deploring the gradual deterioration of Rome’s political culture. Both the ‘manners’ and the ‘men’ have disappeared.”

Cicero is deploring the gradual deterioration of Rome’s political culture. Both the “manners” and the “men” have disappeared: “It is owing to our vices, rather than any accident, that we have retained the name of republic when we have long since lost the reality.”

Critical readers of Cicero hasten to remark that he rather idealizes the Roman Republic — it never was a fully functional political system, and a great many people were crushed under its wheels. However, it was better than dictatorship. Cato is to be preferred to Caligula, Cicero to Nero.

A similar lament could be offered over our country, as we prepare to celebrate the Fourth of July once again. We don’t need to (and must not) idealize American political history to have a sense that some of the better elements of the political culture we inherited have faded badly. Neither the “manners” nor the men and women who now lead us are what they ought to be.

“Having received the commonwealth as a finished picture of another century,” its colors have now faded. Both the norms of politics, and many of the people in politics, represent a marked deterioration. The formal structures designed almost 250 years ago survive, but the ethos of American democracy, the “spirit of the laws” (Montesquieu), has unraveled.

Whose fault is it? “It is owing to our vices,” says Cicero. We are doing this to ourselves.

Cicero witnessed the collapse of the Roman Republic. Will we witness the collapse of the American one? Cicero would say that is up to us.

This article first appeared in Baptist News Global.