A friend sent me this piece in Salon, posted under the provocative title, “How Evangelicals Abandoned Christianity and Became ‘Conservatives’ Instead.” I was not familiar with the author, Nathaniel Manderson, who identifies himself as an evangelical pastor trained at a conservative seminary but guided by liberal ideals.

Manderson’s article basically argues that under the leadership of 40 years of reactionary ideologues, U.S. evangelicals have traded in the love of Jesus for a fear-based, hard-hearted, narrow-minded, right-wing ideology, and this is a disaster. This argument is a familiar one on the Christian left, and I have offered many versions of it myself. I still agree with it, at least with reference to a large number of U.S. white evangelicals.

This month, a nuanced and lengthy study has been published that argues for basically the opposite hypothesis — that it is the religious left that has traded in Christianity, or at least theology, for politics, but this time liberal politics. That claim is found in George Yancey and Ashlee Quosigk’s new book, One Faith No Longer: The Transformation of Christianity in Red and Blue America.

George Yancey is a Baylor University sociologist, and the book is framed as a sociological study. Its principal claim — for which I am quoted, in one of my more incendiary moments — is that Christianity in America is undergoing a left/right split so profound as to create two separate religions. Both these religions are called “Christianity,” but the two sides are no longer anything like a single religious community. Whereas earlier schisms in Christianity had to do with fine points of doctrine, this one is mainly ideological-political.

The book’s most significant — and debatable — secondary claim is that liberals mainly define themselves in terms of social-justice convictions, while conservatives still center on theological claims and define themselves that way. The book, published by New York University Press, fails to sustain its framing sociological objectivity, instead (in my opinion) oozing conservative wonderment over what has become of us liberal Christians.

(Full disclosure: In the draft of One Faith No Longer that I read, I was described as, essentially, a classic theological liberal who has abandoned Scripture for experience. I completely reject this characterization, and said so in dialogue with the authors, who to their credit took my concerns seriously and promised a few edits.)

“Who is in a better position to tell the story honestly about what is happening within these two sides of American religion?”

So which is it? Is it those dastardly conservatives who have traded in true Christianity for their reactionary politics, or is it instead those awful liberals who have abandoned theology for their painfully woke social-justice religion?

Then there is this question: Who is in a better position to tell the story honestly about what is happening within these two sides of American religion — those of us pointing fingers at the bad guys on the other side, or those who are willing to critique the foibles and follies of their own side? Can it be that what we need right now are more internal critics and fewer external finger-pointers?

Is the most salient question simply this: If we grant that American society is dividing, sometimes in a truly frightening way, why isn’t American Christianity demonstrating the ability to do anything other than be swallowed up by the split? Shouldn’t there be resources in our theology, ethics, churches, families, friendships, parachurch organizations and everything else we have built up over centuries that can enable us to help prevent social schism, rather than be consumed by it?

“I am trying to articulate clear theological and spiritual convictions and not just social-ethical and political ones.”

Or is this one of those revolutionary moments in which all morally serious people just head to the barricades, to national Armageddon, in favor of the side they are sure is God’s?

In my own recent work, I am trying to articulate clear theological and spiritual convictions and not just social-ethical and political ones, if only to remind myself and others that Christianity is more than ethics and politics.

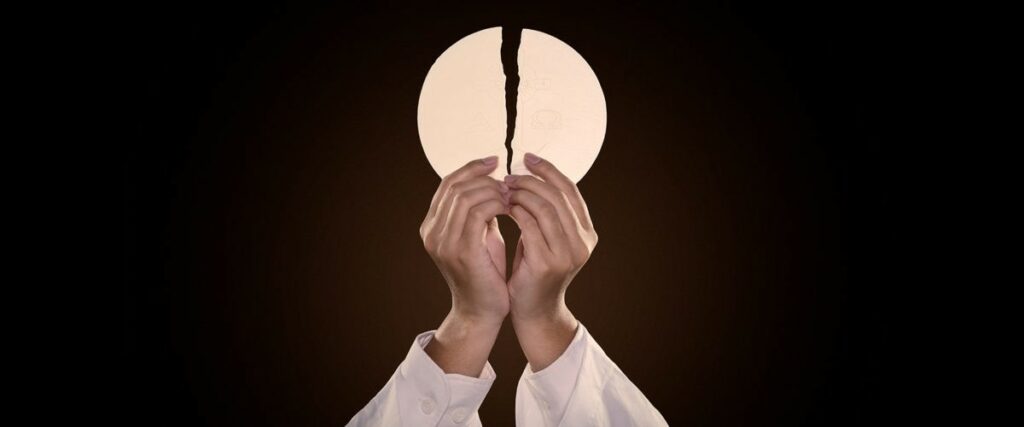

And I am looking for any and every bit of evidence of local churches in which pastors minister to the basic spiritual needs of their flocks rather than drift into politics, members look at each other as sisters and brothers, and congregations become sites of reconciliation rather than further division. I somehow still believe that such reconciliation is at the heart of the gospel.

This article first appeared on Baptist News Global.