This week I begin my 31st year of full-time teaching in the field of Christian ethics. In this post I want to think aloud about the art and craft of teaching.

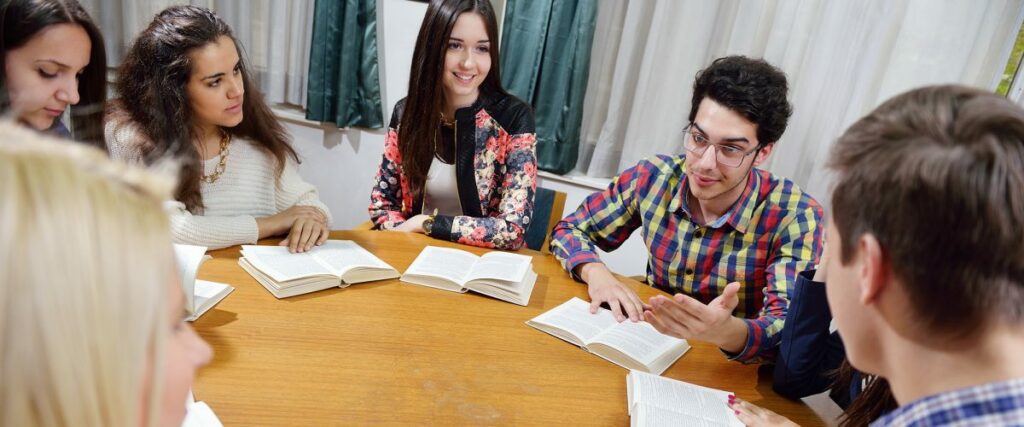

I believe the magic in teaching — at least in the humanities — takes place when a decently gifted teacher works with motivated students to engage significant texts and ideas over the course of an unhurried semester. My metaphor for the ideal classroom is a conference table stacked with great books and surrounded by eager, smart students. That’s education to me, at its core.

A thought about technology seems a timely interruption at this point. I was a late adopter of online education. I never was one who volunteered. I wanted to be around a literal table in a literal room with literal books and embodied students.

While I still prefer in-person education, COVID changed much for me, including recognition of the value of virtual education. Last semester I had students join in from the UK, Seattle, Houston, Huntsville and many places in Georgia. This fall, I will again teach online, and I assume the students will again be in a number of different places.

Online education makes access to education much wider, and access is a good thing. And so, I have adapted, even though online school requires technological mediation of education in ways I will perhaps never fully accept.

Whether online or in person, my vision of the art and craft of teaching does not require grades, policies and long syllabi. Education in its purest form needs none of this. However, back in the real world in the Year of Our Lord 2023, I understand it is not permitted to offer accredited higher education courses without all these accoutrements. But I try to keep my eye on the ball: At its core, at least in my view, the educational enterprise remains the same as it was decades or centuries ago. It is a guided conversation among thoughtful people about great books and ideas.

I did not always understand this. I remember when I was just getting started teaching at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary as a newly minted professor. All my classes were new to me, so that meant three new course preps per semester in the first year. I was a haggard, weary young man, believing it to be my responsibility to write full-length lectures for every class period.

Veterans of Southern Baptist educational life may appreciate this next story. Legendary Southern Seminary professors Wayne Oates and Samuel Southard ran into me in the hall one day during my first term at Southern in fall 1993. They asked me how it was going. I complained of the exhaustion of writing all these new lectures. I think it was Sam Southard who asked me, point-blank, “Why are you writing all these lectures? You don’t have to do that. Involve the students in their own learning experience.”

That bit of wise advice came as a bolt out of the blue.

Somehow, I had imbibed the idea that teaching just was lecturing as comprehensively as possible about the subject and then fielding challenging questions until the time mercifully ended. I gradually learned that the more confident professors did not feel the need to be “sage on stage,” and that teaching was more effective when it was participatory. But this involves a willingness on the part of the professor to accept not always having the floor, not always dominating the conversation, not always having the last word.

This, in turn, reflects awareness that all serious learners in an educational conversation have something to contribute that can enrich the community of inquiry gathered in that room. It also reflects the discovery that there is no last word in any human intellectual endeavor. All education, all conversation, has a fragmentary and incomplete quality, and we do the best we can until the next conversation, when we do it again.

I now will perhaps sound like an old curmudgeon as I offer my lament about the encroachment of bureaucracy in higher education. Each year, it seems, more and more material ends up in syllabi that is not generated by the professor but by university administrators, accreditors and lawyers. My syllabus this semester is an unprecedented 20 pages long. Now, for sure, some of that is of my own devising, but a fair amount is verbiage that comes from outside actors. Today’s higher ed syllabus is more like a contract than it ever has been, and a certain defensiveness now creeps into an educational process that ought to feel free and unhindered by fear. I regret this very much.

I want to close by expressing gratitude that I have had the opportunity to be a professor for all these years. I am fully aware of how many of my colleagues, especially younger and more recent graduates, have been partly or fully blocked from the privilege of exercising the vocation for which they were or are gifted, called and trained.

Religious politics, including in Baptist and evangelical life, tragically foreshortened a number of careers over these last three decades. Meanwhile, today, there are far more qualified professors than there are jobs, especially in the humanities. This is a structural problem in higher education and one that is under constant discussion in professional circles, without much progress.

I simply want to say here that I deeply lament the loss of opportunity and the shattered dreams of many scholars blocked from doing the work they want to do — a work that is so deeply meaningful for those with the calling and opportunity to pursue it.

This article first appeared on Baptist News Global.